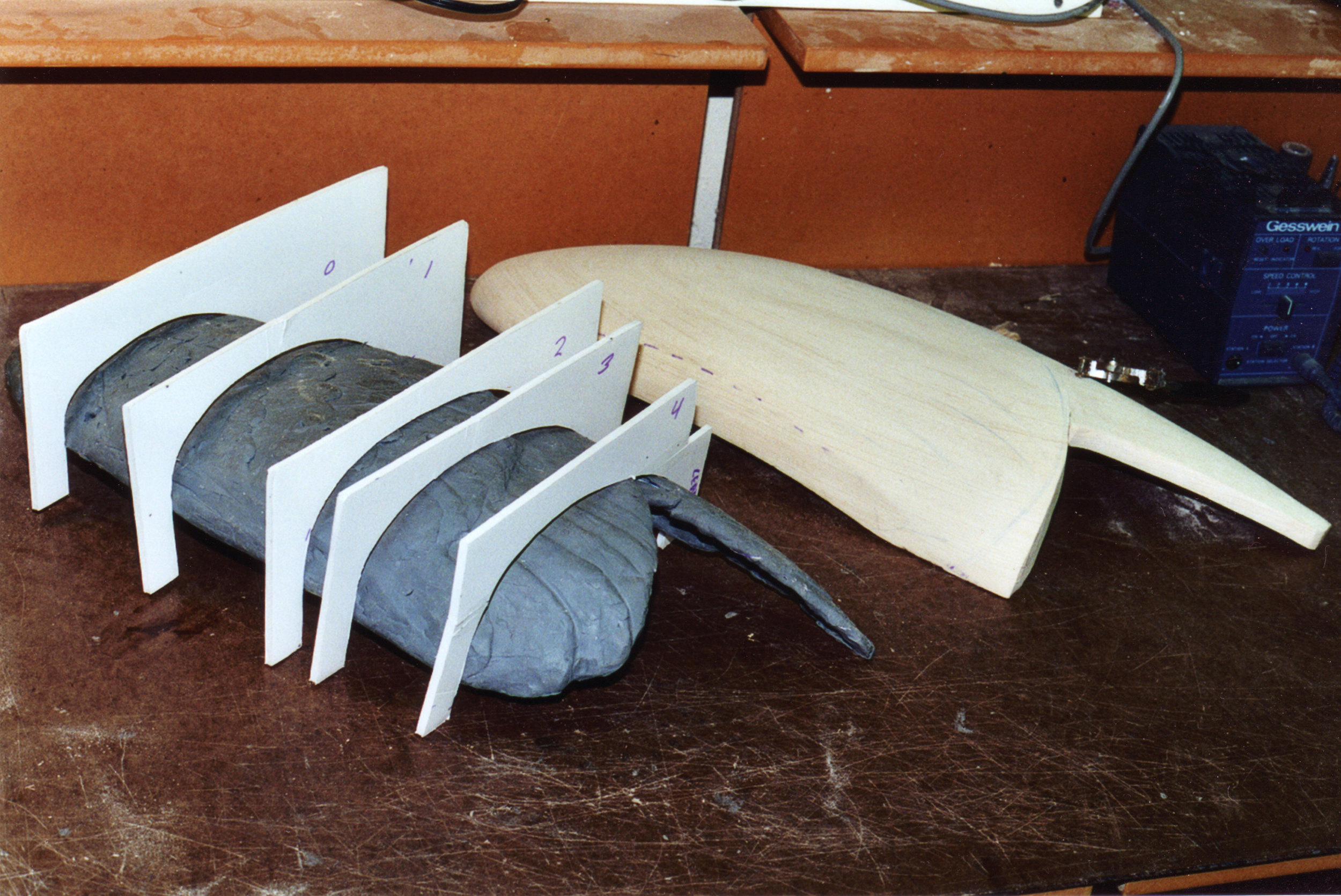

Using scaled templates, a half-sized clay study helps to decide the attitude and configuration of the Eagle. A wooden armature is then used to create a life-sized clay study.

A full-sized clay study provides the guidance and confidence to proceed. Final templates for the wood cutout are checked against the scaled templates created from the half-sized study. Any alterations are inscribed onto the full-sized final templates.

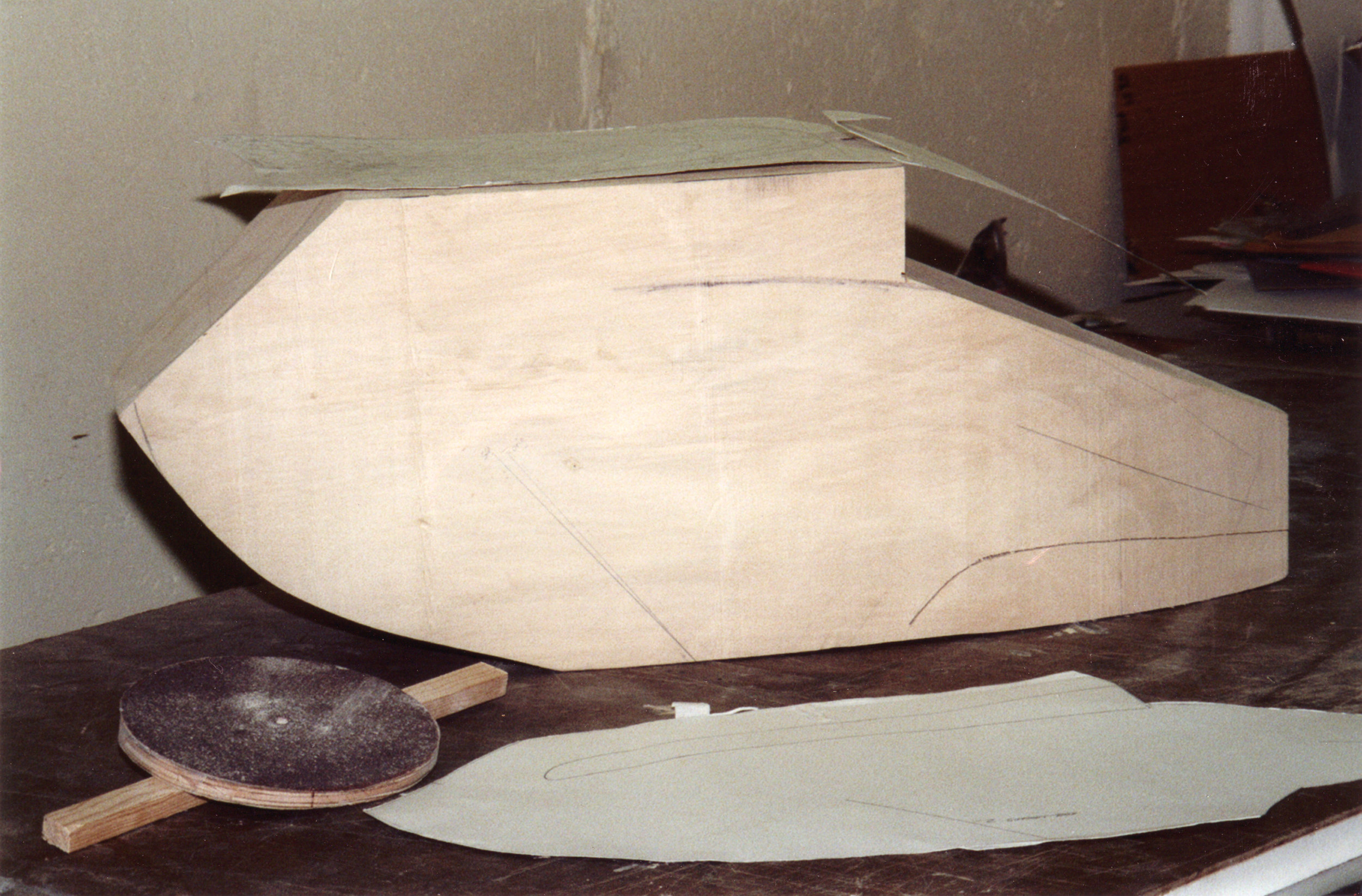

Appropriate blocks of tupelo wood are selected, sized, and squared-off according to their intended use. Top and side pattern cut-outs are drafted in order to maximize the potential for each unique block.

The main body block is cut top and side using a specialized band saw.

The clay studies of auxiliary pieces are transferred to their wood counterparts in preparation for mounting to the main body.

Individual components are mounted into recessed joints and slots in order to make the body one uniform piece.

With all geometric blocks reduced into their recognizable forms, a characteristic bird begins to take shape.

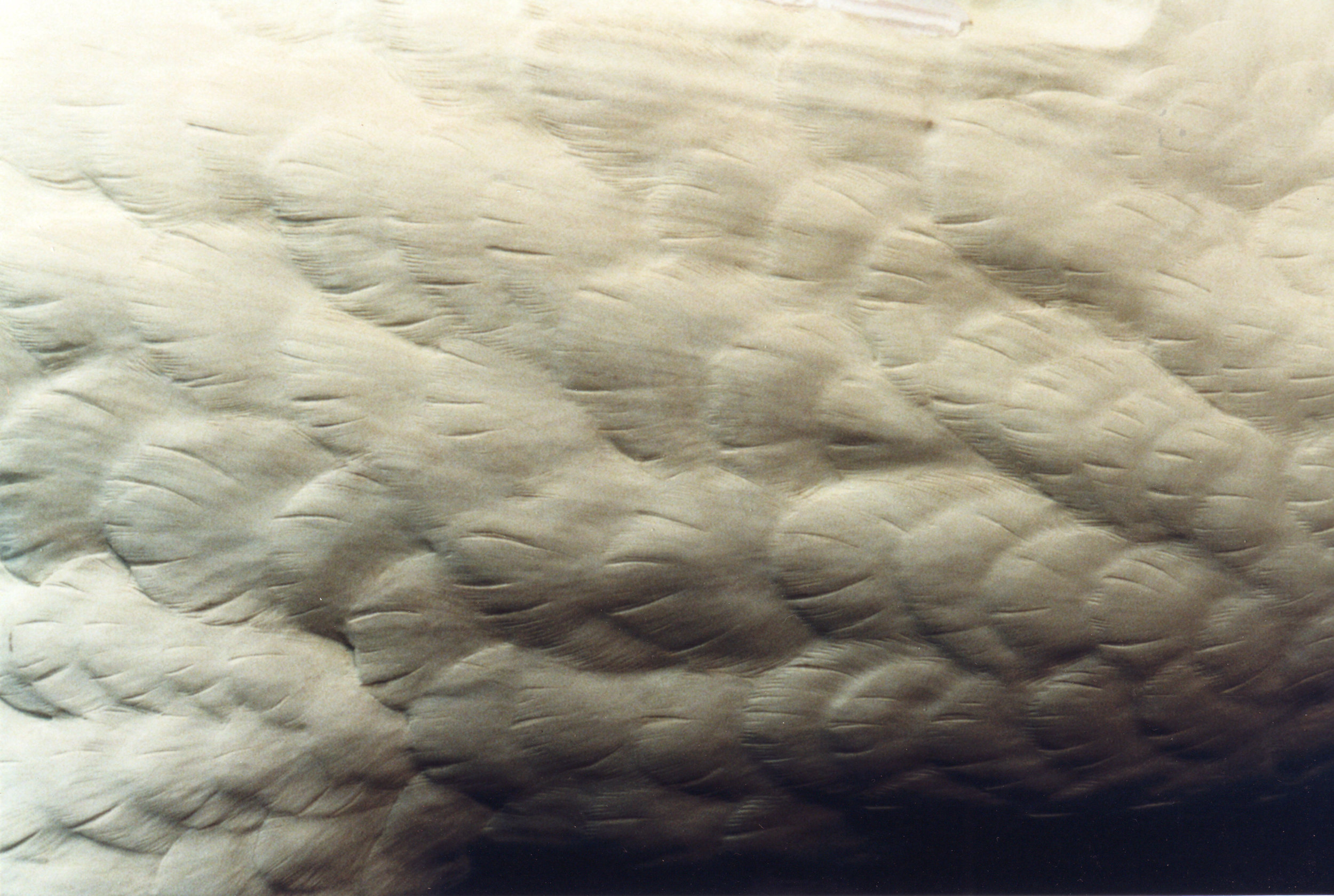

Individual feathers are relieved. This process is done with a high-speed rotary tool equipped with various burrs and diamond mandrels.

Feather splits are cut. Plumage tufts are sanded, to create the illusion of softness.

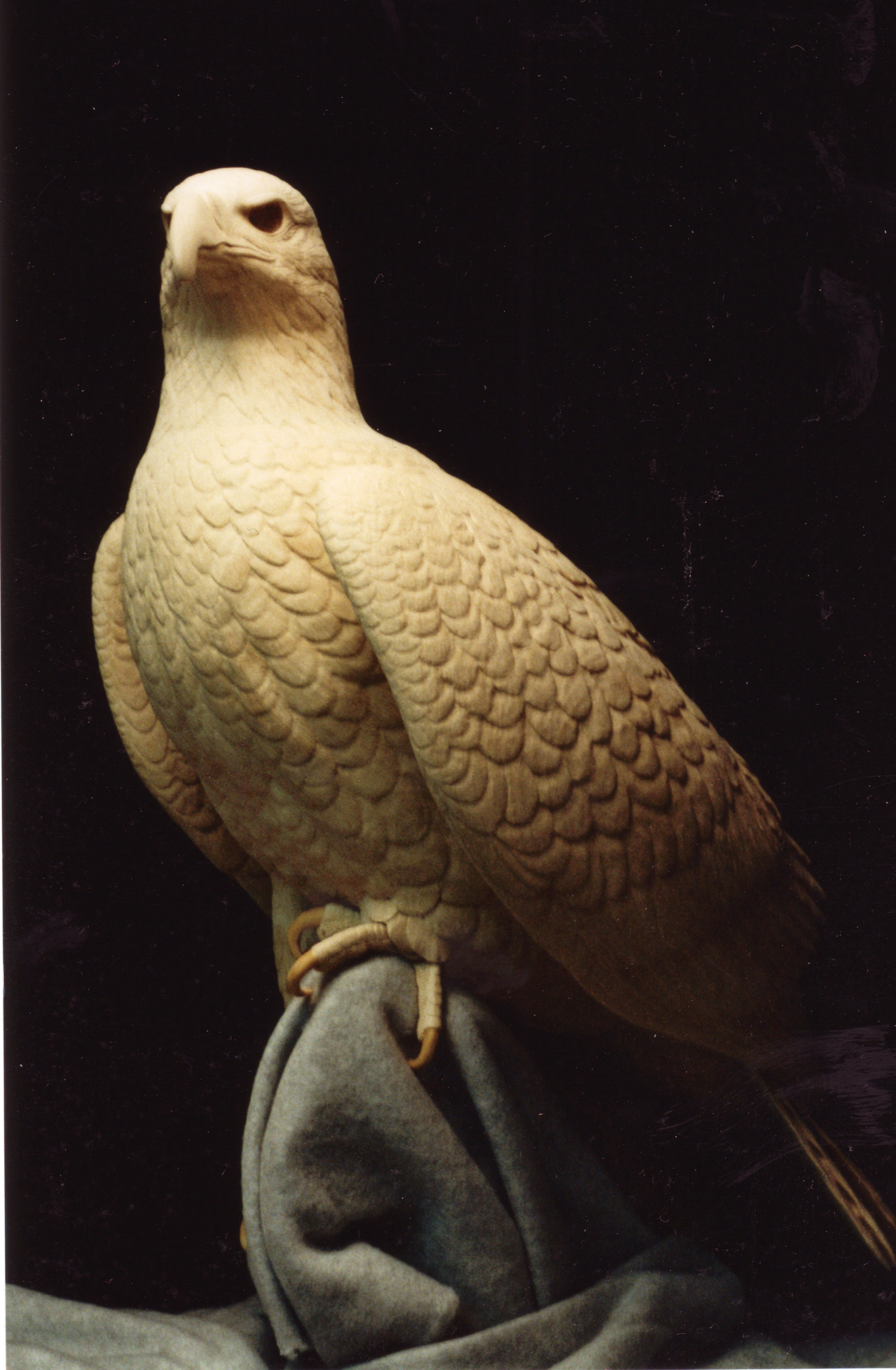

Meanwhile, other parts of the bird are being sculpted. Talons and tail feathers are among the types of parts that are best carved separately and inserted into the body accordingly. By itemizing features into sub-components, greater levels of detail and expression are ensured.

With all components completed, the piece is assembled as a whole for the first time, a big relief after many months of hard work!

A glass eye is set into an epoxy base within the fitted eye socket carved in the head. The angle and depth are critical factors for creating character.

Very fine, hair-like barbules are painstakingly scored into each feather with the use of a specialized burning tool made for pyrographic art. At more than 50 lines per inch, this process, called "burning", makes for tight and tedious work, but the illusion of reality that it creates is unparalleled.

Introspection and critical analysis are constant factors when attempting to simulate reality. Taking a step back and determining the best course of action is paramount for an impressive outcome. This is especially true during the burning process where the feathers need to be anatomically-correct, but also follow a pattern that compliments the posture of the overall pose. Even without paint, the feathery look emerges from the wooden forms.

Larger pieces such as this Eagle are first painted in sections, a strategy that makes intense detail work more practical to accomplish. In this photo, the head head is nearly ready to attach. Artist oils will be gradually built-up in thin glazes over the head and body over the course of several weeks.

The process of painting the body starts with large blends of color. With individual passes completed over successive days, hues and values are added strategically. Patterns of color tighten, and become neater. It can take more than six glazes of oil in order to establish the proper opacity for specific blends of colors.

The dorsal view of the painted Eagle.

A detail of the talons.

Completed 2005, Eric M. Kaiser